Islamic architecture and design long captivated the West, but during the 19th century this interest was renewed as Britain and France came increasingly into contact with the Muslim world. A large number of books began appearing from the 1830s, documenting Islamic (or as it was called back then “Arab”) architecture and the diverse styles of ornament—geometric, calligraphy, and figural representation particularly in Egypt and southern Spain.

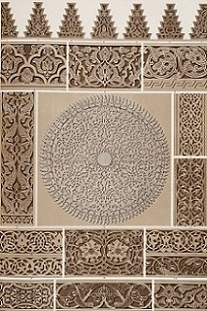

Owen Jones (1809–1874) was among the first British architects and designers to record Islamic ornament in detail, following a trip he took at age 23 to Italy, Egypt, Greece, Turkey, and Spain. During his time in this last country together with the French architect Jules Goury (1803–34), Jones visited the famous Alhambra Palace in Granada, and produced a series of studies of the palace’s architecture and decorative details. The magnificent two-volume publication Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra (1842–45) brought Jones to the attention of a broad audience, and he collaborated with Prince Albert’s work on the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851 in London. The Great Exhibition helped to popularize foreign art and design to the British public, paving the way for Jones’ 1856 publication, The Grammar of Ornament (1856). This lavish work includes 20 chapters, each with explanatory text on ornaments from very different sources, including Greece, China, Medieval Europe, and the Islamic world. In his book, Jones established 37 propositions or guiding principles for the “arrangement of form and color,” in an effort to save Victorian design from its perceived decline. Forms of nature, according to Jones, also inspired the best ideas, such as in Arabian No. 3, featuring exquisite vegetal patterns in the ornament decoration of various Cairo mosques.

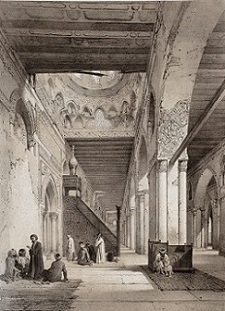

Like Jones, French engineer, artist, writer, and Egyptologist, Prisse d’Avennes was also a proponent of Islamic design, seeking the revitalization of Western aesthetics. Initially an engineer and professor of topography in Egyptian military schools from 1827 to 1836, 1836, he resigned his post to pursue his passion for Pharaonic and Medieval Islamic monuments. For the next 17 years he traveled throughout Egypt and elsewhere in the Near East, and he came back later for another two years. Returning to France, Prisse published several books including one of the most comprehensive sources of information on Islamic architecture and design of Cairo, Arab Art According to the Monuments of Cairo from the 7th Century to the End of the 18th (1869–77). Its exquisite three illustrated volumes (called the Atlas) with 200 large color and engraved plates, as well as a 300-page text volume detail the interiors and exteriors of mosques, such as the Mosque of Ahmad Ibn Tulun and other important structures as well as examples of ornaments. A few plates, like Arabesque, however, are Prisse’s own decorative inventions comprising different types of arabesques from wooden compartments and borders. Prisse deeply appreciated the Islamic style, especially that of Egypt and Syria, and suggested that its superiority could save Europe from then-current “poverty of invention.” Despite its significance and preliminary success, sales of the publication faltered, and copies eventually disappeared into national libraries and private collections.