“[A]rt runs forward in all directions on wings of steam; new lands, unexplored climates, unfamiliar human types, original races offer themselves to art from every angle,” wrote Théophile Gautier in 1857 in the journal L’Artiste. Western interest in classifying human “types” according to their facial physiognomies and distinctive costumes goes back to the 16th century, but by the second half of the 19th century the portrayal of ethnic groups was a prolific theme in Orientalist art. Improved and newly invented forms of transportation made the Orient (present-day Turkey, the Middle East, and North Africa) more accessible, prompting a flood of artists to head for that region and produce realistic representations of its diverse populations. The new discipline of ethnography, as well as the display of different foreign peoples in Universal exhibitions in the various European cities, was crucial in fueling the popularity of such images.

Charles Cordier (1827–1905) was among the most famous 19th-century French ethnographic sculptors. A pupil of François Rude (1784–1855), Cordier devoted his career to portraying diverse human races. From 1851 to 1866 he created a series of busts for the Paris Museum of Natural History’s new ethnographic gallery as its official ethnographic sculptor. He received a number of government grants for missions in Algeria (1856), Greece (1858), and Egypt (1866) to study and reproduce in sculpture “the different indigenous types of the human race.” But aside from documenting racial differences, Cordier’s main goal was to “present the race as it is in its own beauty, absolutely true to life, with its passion, its fatalism, in its quiet pride and conceit.” A Sudanese in Algerian Costume is one of Cordier’s most successful works exemplifying this approach. The Dahesh sculpture is a reduced version of the silvered bronze and onyx sculpture that was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1857 and purchased by Emperor Napoleon III (Musée d’Orsay, Paris).

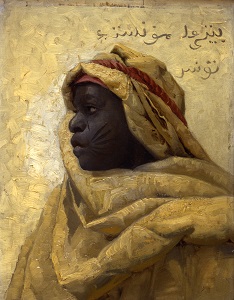

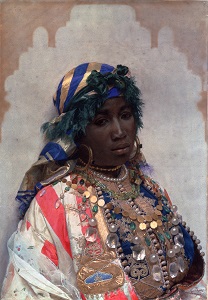

Interest in ethnography continued into the late 19th century. Like Cordier, numerous artists rendered careful studies of physiognomy and costume, while capturing the essence and expression of the individuals. An example is Peder Mønsted’s (1859–1941) sensitive portrait of a cloaked Nubian—the Nubians live in southern Egypt and present-day Northern Sudan—conveying a sense of strength and dignity. Best known for his Nordic landscapes, Mønsted trained at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, Denmark from 1875 to 1879 and later traveled extensively throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. In 1876 José Tapiró y Baró (1836–1913), the first painter from Spain to settle in Tangier—in northern Morocco across the Strait of Gibraltar—produced numerous watercolors of indigenous North Africans. An iconic example is A Tangerian Beauty, painted around 1891, in which the artist captures the sitter’s likeness and expression, and emphasizes the vibrant colors and textures of her costume and accessories—echoing the work of his childhood friend and celebrated Spanish artist Mariano Fortuny y Marsal (1838–1874). A further typical work is Head of a North African Woman by another colleague of Fortuny, Nazzareno Cipriani (1843–1925). While the Italian artist specialized in Venetian scenes, he likely turned to this theme because of the high demand for these images in contemporary Rome. The careful study of physiognomy, close attention to costume, and focus on personal characteristics align this watercolor with the ethnographic work of Cordier, Mønsted, and Tapiró. The woman’s somber contemplative expression as well as her striking clothes and jewelry are all superbly captured by Cipriani, lending the image an extraordinary immediacy.