The Board of Trustees and staff of the Dahesh Museum of Art remember with great pleasure our inaugural opening 25 years ago. It was very festive but just the beginning of a long-term goal of celebrating Academic Art. We are grateful for the support you and museum colleagues everywhere have provided. We have heard your good wishes through the years and will continue to pursue our mission. Thank you for your patience as we plan an exciting future.

Gérôme’s Working in Marble to Complement Van Gogh Self-Portraits in Amsterdam Exhibition

How do artists view other artists — and themselves? That is the question Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum is posing in an exhibition opening February 21, where one of the Dahesh Museum of Art’s best-known paintings joins other masterpieces in response to that query.

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s intricate composition of himself in his own studio, Working in Marble or The Artist Sculpting Tanagra, should be one of the most informative works accompanying the many chosen to hang in this exhibition, titled In the Picture—Artists’ Portraits. In addition to an extraordinary selection of Vincent van Gogh self-portraits, works by Paul Gauguin, John Peter Russell, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and others will explore how, why, and with what impact images of the artist have contributed to both the making and viewing of the portrait.

The exhibition examines several themes — The Image of the Artist, Up Close and Personal, The Suffering Artist, and The Artist at Work. Gérôme’s self-depiction is a prime

example of the last category, the artist surrounded by exactly painted objects related to his art and life. In addition to the well-known sculpture, now in the Musée d’Orsay collection, we see other examples of his art, such as The Hoop Dancer, Gérôme’s personal version of fourth-century B.C. terra cotta figurines that were found during 19th-century excavations of Tanagra tombs. Their realism, and the fact that many were painted, led to a re-evaluation of subject matter and color in Classical and Hellenistic Greek sculpture, as well as a movement to add color to contemporary sculpture. A 1997 exhibition at the Dahesh Museum, Jean-Léon Gérôme and the Classical Imagination, included a marble version of the Tanagra figure’s head with subtle tinting (Santa Barbara Museum of Art). We also see on the wall a small version of his painting Pygmalion and Galatea, a delicious composition that wittily comments on Gérôme’s use of a living model in creating the life-size Tanagra figure.

|

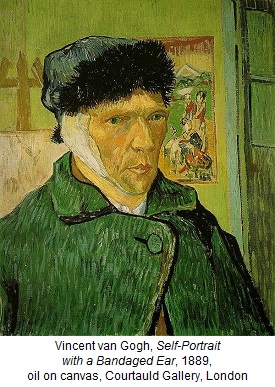

In the Picture features Vincent’s famous Self-Portrait with a Bandaged Ear from the Courtauld Gallery in London, hanging with 17 self-portraits from the Van Gogh Museum collection. Any one of these will seem a startling contrast to the Dahesh Gérôme. Historically, the two artists’ work represents a turning point in art history — emphasized by the simultaneous 1890 date of Gérôme’s painting and Van Gogh’s death. Working in Marble is a manifesto of 19th-century academic practice, meticulously describing an artist’s creative environment and process, including both Classical and Oriental props he collected that sometimes reappear in his paintings, while Vincent’s self-portraits are unsparingly focused on his face, expressionistically painted studies of the artist’s psychology. Self-Portrait with a Bandaged Ear, however, provides something more, a glimpse of his artistic interests. The Japanese print in the near background, identified as Geishas in a Landscape, published by Sato Torakiyo in the 1870s (one of many he owned), reminds us that Japanese art, especially woodblock prints, enormously captivated and influenced Van Gogh and European Modern art in general. This interesting similarity only emphasizes the differences between the contemporaneous work of the two artists — modernism arriving with a vengeance.

The exhibition can be seen through August 30.

From its earliest days, the Dahesh Museum of Art has deliberately collected and studied artists’ portraits and self-portraits. Gérôme’s Working in Marble was purchased shortly after the Museum opened and remains one of its most important paintings. A masterpiece of realism by the greatest of late 19th-century academic painters, it extols the formal ideals valued by the academy, letting us into his studio to see how his art was actually achieved.

The Museum’s goal continues to be study of portraiture’s diverse stylistic approaches and mediums — paintings, drawings, sculptures, and medals — and documenting their importance in the history of art. Alia Nour, the Museum’s Curator, has been researching this aspect of our collection and developing a future exhibition. We present here four examples that we hope will whet your appetite.

Academic art valued the work of artists from the past and often represented those figures in imaginative ways, such as Gérôme’s Blind Michelangelo Being Shown the Belvedere Torso, 1849 (he was never blind!), and Paul Delaroche’s Peter Paul Rubens and Pierre Puget, pencil and charcoal studies for two of the many artists represented in his immense hemicycle in the École des Beaux-Arts, Paris (surely the most ambitious of all artists’ portraits). John Ballantynes’s David Roberts and his Grandson in his Studio, 1864 (not his granddaughter, as sometimes wrongly identified), takes us into recent art history.

Roberts is best known as a pioneer artist-explorer of the Middle East and Egypt in the early 19th century, a test of endurance and logistical fortitude. From his many sketches, he published spectacular (and technically innovative) lithographs that set the standard for subsequent Orientalist artists and nicely represented in the Dahesh Collection. Here, however, we see him much closer to the end of his life, an established Victorian gentleman enjoying his success and grandson, Gilbert, who is dressed in conventional mode for very young boys that is often mistaken for a girls’ outfit. The painting is from Ballantyne’s series of “At Home” views of London artists, favoring fellow Scots.

The history of self-portraits is, of course, a long one, and some artists seem more inclined to experiment than others — Van Gogh being a principal example and Rembrandt another. The academy’s emphasis on drawing established the graphic self-portrait as an excellent and logistically simple method of study, and the Dahesh collection includes a fine group of such works. Any survey of drawn self-portraits will suggest each individual’s personality and, even in a strictly academic approach, there will be significant differences in style and technique. Alexandre Rapin’s intense and elegantly finished graphite work, for instance, displays the exacting descriptive realism of his training with Gérôme. His evident skill, however, served him ultimately as a painter of moody landscapes, a career that won him honors as it took him far away from historical subject matter.

A charming Self-Portrait with Palette and Brush by Émile Friant proposes an artist of a different sensibility. We meet the same intense gaze in his and Rapin’s work, but Friant’s lively linear style arouses our suspicion that he is not entirely serious in this process. And, in fact, after studying with the history painter Alexandre Cabanel, Friant left Paris for his native Nancy and associations with other Lorraine artists who preferred images of everyday life, painted with admirable visual truth in describing native customs and pleasures. Like Rapin, he won honors and success in a life far from Paris. It is inscribed A notre ami et admirateur/ enthousiaste Edmond Neille/le portrait d’auteur/ami –prix de Rome /E. Friant — a very personal gift to a friend.

|

Among the most curious works in the Dahesh Museum is Louis Abel-Truchet’s

Trompe l‘oeil of a Painter. Like Friant’s self-portrait, we know the subject is an artist because he is holding a palette (conveniently signed Abel Truchet). Is this life-size figure a painting or a sculpture? It is painted but also a free-standing representation, although two-dimensional. Like all self-portraits, he looks directly at us, as in a mirror. But is that really Abel-Truchet, his appearance otherwise only generally described and employing a technique rather different from his known paintings?

Whatever its definition, it certainly does “fool the eye” (the English translation of trompe l’oeil) and was featured in a recent spectacular exhibition in Munich, Thrill of Deception, organized by the Dahesh Museum’s former Curator Roger Diederen. More discussion about this and other portraits will be forthcoming in the exhibition, so stay tuned to our regular online announcements.

Connect with us

|

|

|