Learning to render emotions through facial expressions was an essential part of the training offered to students at the École des Beaux-Arts in the 19th century. Just as these pupils studied composition and anatomy, they also made detailed examinations of faces in an attempt to master the depiction of human emotions. This practice evolved out of a lecture given in 1688 by Charles Le Brun, a founder of the French Royal Academy, who used a theory from René Descartes’ Treatise on the Passions to argue that there was a link between muscles and expressions. Copies of Le Brun’s lecture, accompanied by his numerous, schematized drawings of faces demonstrating emotions, were disseminated to various art schools. Students heeded Le Brun’s teachings, and began learning to draw emotions by copying his drawings (Louvre) as well as faces from antiquities, such as the anguished visages in Laocoön and His Sons (Pio Clementino Museum, Vatican).

Le Brun’s theories were formally institutionalized at the Academy in 1759, when the Comte de Caylus established the “Expressive Head Competition,” a drawing contest that encouraged students to learn how to represent emotion. Caylus, however, felt that copying emotions from works of art produced mannered and repetitive results, and so the competition required students to draw from live models, who mimicked the emotions and poses of Le Brun’s expressive heads. The competition rules indicated that the models should embody “la belle nature,” which at that time, meant young beautiful, virtuous women with no trace of life experiences in their face. The competition became one of the most prestigious at the Academy, and grew to encompass painting and sculpture as well.

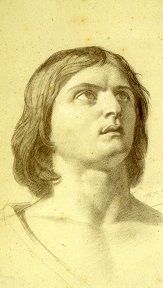

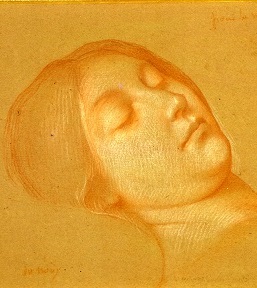

Of course, after their education artists continued to represent emotion and facial expression––most importantly as head studies in the preparation of finished works. For instance, Léon Benouville, who won second (1843) and first place (1844) prizes in the contest, drew his Study of a Man’s Head in Profile (2002.27) possibly as a study for his painting Oedipus exiled from Thebes (location unknown). Michel Dumas’ Head of a Youth (2001.15), a study for his masterpiece, The Parting of Saint Peter and Saint Paul Before Their Martyrdom (1852, Louvre, Paris), and Jean-Antoine-Jules Lecomte du Nouÿ’s sketch for The Death of the Virgin (2001.14), a study for one of a series of frescoes for the chapels and choir of the Church of Saint Nicholas at Iasi, Romania, and are also good examples of the careful preparation undertaken by the artist, as they used their pencils to translate the model’s emotion and mental state onto the page. Pierre Jules Cavelier created this bust of Tragedy (2003.12), which combines a study of a head with an Ancient Greek theatrical mask, as a second year envoi, a work made by Prix de Rome winners to demonstrate their artistic development. Cavelier was evidently proud enough of this bust to exhibit a bronze version (location unknown) again at the 1855 Universal Exhibition.